The term “dopamine addiction” is thrown around online, in self-help content and social media—but it’s not a medical diagnosis in the UK. When people use this term, they’re usually describing compulsive, reward-seeking patterns of behaviour that feel hard to control.

To be clear from the start: dopamine itself is not addictive. It’s a naturally occurring brain chemical that’s involved in motivation, learning and movement. But the patterns of behaviour around activities that release dopamine can become problematic for some people.

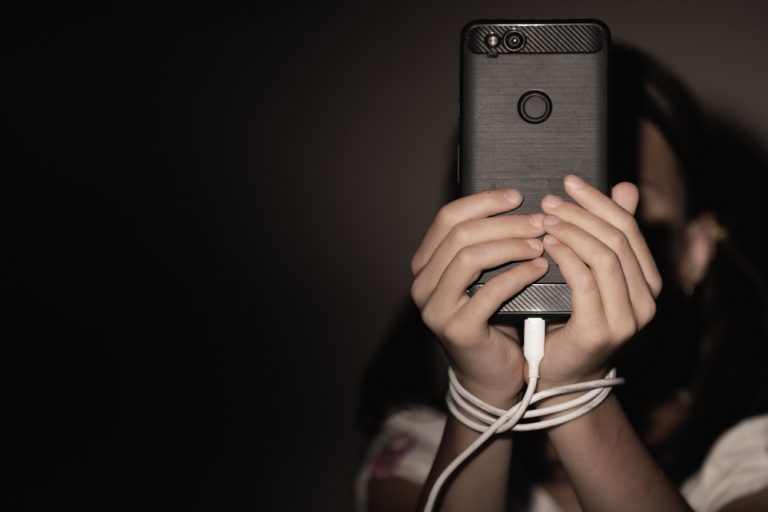

You may recognise the feeling: scrolling through social media at 2am when you meant to sleep hours ago, gaming late into the night despite work the next morning, or checking betting apps even after deciding to take a break. These are common and understanding what drives them can be the first step to change.

This article explains what dopamine actually does in the brain, why the term “dopamine addiction” became popular and the signs that reward-seeking behaviour may be getting out of hand. Throughout, it’s about accurate, balanced information not quick fixes or drama.

What Dopamine Does in the Brain

Dopamine is a chemical messenger—a neurotransmitter—that nerve cells use to talk to each other. It’s often called the “pleasure chemical” in the media, but that’s not entirely accurate. Dopamine plays a much broader role in how the brain works day to day.

Here’s what dopamine is actually involved in:

Movement and coordination: The brain’s dopamine system controls physical movement. Conditions like Parkinson’s disease involve the loss of dopamine-producing cells, resulting in tremors and stiffness.

Motivation and drive: Dopamine helps you feel motivated to pursue goals. It creates the sense of “wanting” something, which is different from actually “liking” or enjoying it once you have it.

Learning from experience: When something feels rewarding—passing an exam, winning a football match, getting a message from a friend—the brain releases dopamine. This helps encode the memory and signals “this mattered; do it again.”

The brain’s reward system: The mesolimbic pathway connects areas including the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and nucleus accumbens. When you encounter something rewarding, dopamine signals travel along this pathway, reinforcing behaviours that helped you get that reward.*

Cognitive functions: Dopamine is involved in attention, working memory and decision-making through its connections to the prefrontal cortex.

The brain releases dopamine every day in ordinary activities—eating a meal, walking the dog, having a conversation or completing a task. These are part of normal functioning and dopamine is essential for a balanced, motivated life.

Note that dopamine is also involved in mental health conditions like ADHD and some psychotic disorders but this article focuses on reward and behaviour not neurological disease.

Why People Use the Term “Dopamine Addiction”

The phrase “dopamine addiction” became popular in the media and social networks around the late 2010s often alongside concepts like dopamine fasting or “dopamine detox”. You may have seen claims about “resetting your dopamine in 90 days” or that modern life has “hijacked” your brain’s reward centre.

UK clinical services—including the NHS and NICE—do not use “dopamine addiction” as a formal diagnosis. Instead they recognise specific conditions such as substance use disorders and behavioural addictions like gambling disorder.

So why has the term become so widespread? Several factors contribute:

Describing a relatable experience: People use the term informally when they feel “hooked” on high-stimulation activities like TikTok, online gaming or sports betting. These activities trigger dopamine release repeatedly and the term captures the sense of compulsion.

The contrast effect: When someone repeatedly engages with very strong rewards, ordinary activities can feel flat or boring by comparison. This happens partly because dopamine receptors adapt to intense stimulation—they become less sensitive over time. People interpret this as “my dopamine is broken” even though the reality involves complex brain adaptations rather than simple deficiency.

Simplified explanations spread easily: Ideas like “dopamine fasting” offer appealingly simple solutions. However the brain’s reward system involves multiple neurotransmitters, regions and processes. There is no single, evidence-based “reset clock” that restores dopamine balance in a predictable timeframe.

When addiction is genuinely present it involves far more than dopamine alone. Genetic factors, personal history, environment, other brain systems and psychological aspects all contribute. Framing everything as “dopamine addiction” oversimplifies a complex picture.

Commonly Reported “Dopamine Addiction” Symptoms and Signs

Before we get to the list, a note: these are descriptive patterns people report, not diagnostic criteria. Reading through them is not a substitute for professional assessment and experiencing some of these patterns does not necessarily mean you have an addiction or mental health condition.

Behavioural patterns people often describe

Many people label certain experiences as “dopamine addiction symptoms”. Common examples include:

Spending far more time than intended on an activity—telling yourself you will watch one video, then realising an hour has passed

Repeatedly checking phones, apps or websites even when nothing urgent is expected

Feeling restless, irritable or “flat” when unable to access a preferred activity (no Wi-Fi, device confiscated or during a self-imposed break)

Struggling to stop or cut down despite repeated decisions to do so—for example, deleting an app and reinstalling it later the same day

Needing more of the activity to achieve the same effects you used to get from less (tolerance)

Emotional experiences

The emotional side often follows recognisable patterns:

Brief surges of excitement, relief or “numb escape” while engaged in the activity

Low mood, guilt or shame afterwards especially if responsibilities were avoided

Preoccupation or daydreaming about the next opportunity to engage

Persistent feelings of restlessness when trying to abstain

Mood swings connected to access or denial of the activity

Social and practical consequences

When patterns intensify they often affect daily life:

Being late for work, missing lectures or cutting sleep to stay online or keep playing

Withdrawing from face-to-face relationships in favour of screen-based activities

Money problems where gambling, in-game purchases or online shopping are involved

Avoiding previously pleasurable activities because they feel boring compared to the high-stimulation alternative

A word of caution: some of these patterns can also appear in recognised mental health conditions like depression, anxiety or ADHD. If these experiences are persistent or causing significant distress discuss them with a health professional.

Examples of Dopamine-Driven Behaviours in Everyday Life

Many normal, harmless activities involve dopamine release—that’s how the brain’s reward system works. Problems arise when patterns become excessive, rigid or cause clear harm to health, relationships, work or finances.

Here are concrete examples relevant to UK daily life:

Activity

How it works

Social media (Instagram, TikTok, X)Likes, comments and short-form video scrolling provide unpredictable rewards that encourage frequent checking. The variable reinforcement is like gambling.

Online gaming (battle royale, MMOs)

Levels, loot boxes and ranking systems give repeated “wins”. The dopamine rush from achievement makes it hard to log off.

Sports betting and casino apps

Rapid bets on football, horse racing or virtual games give fast cycles of risk and reward. Losses trigger cravings to bet again and “chase” the loss.

Online shopping and flash sales

Discounts and next-day delivery give quick bursts of satisfaction especially when feeling low or stressed.

Streaming services

Autoplaying the next episode encourages binge-watching into the early hours and disrupts sleep patterns.

Beyond digital examples, more traditional activities can follow the “chasing the next reward” pattern:

Eating highly processed junk food for quick dopamine hits

Compulsive pornography use or casual sex seeking novelty and intensity

Risky behaviours that give adrenaline alongside dopamine rewards

For most people these activities are part of a balanced life. Concerns arise when they crowd out sleep, work, study, relationships or physical health—when life starts to revolve around seeking the next reward.

When These Symptoms Overlap with Recognised Addictions or Mental Health Conditions

Only trained clinicians can diagnose conditions such as gambling disorder, substance use disorder, depression, bipolar disorder or ADHD. However understanding potential overlaps can help you have more informed conversations with health professionals.

Recognised addiction diagnoses

Repeated high-dopamine behaviours can in some cases overlap with formally recognised conditions:

Gambling disorder: Characterised by increasing bets, chasing losses, borrowing money and lying about gambling. Drug abuse and alcohol addiction often co-occur with gambling problems.

Gaming disorder: Described by the World Health Organization as a pattern where gaming takes priority over other activities and continues despite clear harm.

Substance use disorders: Addictive substance use—whether involving alcohol, cocaine, opioids or other drugs—directly and powerfully affects dopamine pathways. Drug addiction and alcohol addiction involve pronounced dopamine production changes and receptor adaptations.

Mental health conditions with similar patterns

ADHD

People may seek stimulation or novelty, switching rapidly between apps or activities. The brain’s dopamine system works differently in ADHD.

Depression

Someone might use social media, streaming or food addiction patterns to escape low mood or numbness. Anhedonia – the inability to feel normal pleasure – is a hallmark symptom.

Anxiety disorders

Repetitive checking or scrolling can temporarily soothe worry. Environmental cues may trigger cravings to engage in the soothing behaviour.

Bipolar disorder

During certain phases people may engage in risky behaviours, excessive spending or compulsive behaviours that mirror addictive patterns.

What clinicians actually assess

The presence of “dopamine addiction-like” symptoms doesn’t mean someone has an addiction or a specific diagnosis. In UK practice, clinicians look at:

Impact on functioning (work, study, parenting, relationships, physical health)

Duration of problems

Attempts to cut down and results of those attempts

Presence of withdrawal symptoms when stopping

Whether the behaviour continues despite negative consequences

Clinicians don’t measure dopamine levels directly. Assessment focuses on the practical impact of behaviours and the person’s subjective experience.

Recognising Patterns in Your Own Behaviour

Self-reflection without judgment can be a good starting point. Many people noticed changes in their tech and reward-seeking habits during and after the 2020-2021 COVID-19 lockdowns. Screen time increased for most of the population and some of those patterns persisted.

Questions to ask yourself

Ask yourself:

How often do I do this activity longer than I planned?

What important things am I putting off or missing because of it?

How do I feel just before, during and after I do it?

What happens if I take a break for a day or two?

Do I need more dopamine rewards from this activity than I used to in order to feel satisfied?

Small experiments

Rather than trying to make big changes, try small ones to see how easy or hard they feel:

Keep your phone in a different room overnight

Leave bank cards elsewhere while watching sport (to reduce impulsive betting)

Schedule specific gaming hours rather than open-ended sessions

Turn off autoplay on streaming services

Eat at regular times rather than grazing when bored

Finding it hard to make these changes is common. It doesn’t mean you’ve failed or lack willpower. Many of these activities are designed to boost dopamine, hold your attention and encourage repeated use. Exercise, on the other hand, is a more sustainable way to increase dopamine naturally.

Keep a simple diary

A week-long diary of time spent, money spent and mood before and after can help you see patterns you might otherwise miss. This can also make conversations with your GP or therapist more concrete and productive. Instead of saying “I think I might have a problem” you can share specific data about your behaviour.

When to Seek Help and What to Expect

Noticing a problem early and asking for help are positive, protective steps. Many people worry about being judged or feel their concerns aren’t “serious enough”. In reality speaking to a professional when patterns first become concerning often leads to better outcomes.

Clear signs it may be time to seek help

Consider speaking to a professional if:

You can’t cut down and it’s affecting sleep, work, study or home life

You’re hiding the extent of your behaviour, spending or substance use from people close to you

You’re experiencing significant distress, low mood, anxiety or thoughts of self-harm

Money, legal or relationship problems are developing because of the behaviour

You have significant mental health issues alongside the behavioural patterns

You need help to manage withdrawal symptoms when you try to stop

UK first steps

There are several ways to access support:

Contact your GP: Be open about your concerns. GPs can screen for mental health conditions or addiction issues and discuss options including referral to specialist services.

NHS self-referral services: In England, talking therapies (IAPT) services often accept self-referrals. Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have equivalent local mental health services. Talk therapy and cognitive approaches can help many people develop coping mechanisms.

National helplines: NHS 111 provides urgent but non-emergency advice. Specialist helplines exist for gambling-related concerns (such as GamCare) and drug misuse or substance abuse.

Support groups: Peer support can help people develop coping mechanisms and feel less alone. There are groups for various behavioural addictions and substance-related concerns.

Private rehab and specialist treatment: Your GP or primary care provide can also refer you to private rehabilitation centres or specialist addiction services, where tailored treatment plans and medical support are available to address complex cases or when faster access to care is desired.

What assessment involves

A clinical assessment will usually ask about:

Patterns of behaviour (frequency, duration, triggers, environmental cues)

Mood and mental health

Sleep

Physical health

Substance use (drugs, alcohol)

Impact on daily life, relationships, work

Assessment doesn’t involve measuring dopamine levels or dopamine activity directly. Clinicians focus on your experience and its effects on your life.

What support may include

Evidence-based support often involves a combination of approaches:

Therapies: CBT and motivational interviewing are common. These address the psychological aspects of compulsive behaviours.

Practical support: Work on routines, sleep and replacing problematic activities with dopamine boosting activities (e.g. exercise or social connection).

Medical care: If relevant, this may include support for drug misuse, dopamine agonists if prescribed for other conditions or treatment for co-existing mental disorders.

Aftercare and ongoing support: Recovery is often a gradual process. Maintaining balance requires ongoing attention and sometimes continued professional input.

A note on brain adaptability

Research shows the brain can adapt and recover. Dopamine receptors that have been downregulated through chronic stimulation can gradually return to normal sensitivity—though this takes time and varies between individuals. Full restoration of dopamine balance is not immediate, but change is possible.

The concept of dopamine deficiency as a permanent state is a myth. With reduced exposure to supernormal rewards and engagement in healthier activities, many people find ordinary pleasurable experiences become satisfying again.

Many people at some point feel “stuck” in reward-seeking habits. Whether it’s endless scrolling, gaming sessions that go late into the night or more directly harmful behaviours involving gambling or substances, feeling unable to stop is more common than you think.

Understanding dopamine’s role in these patterns—without oversimplifying it as “dopamine addiction”—can help you make sense of what you’re experiencing. The brain’s reward system evolved to help us survive and thrive, not to trap us in compulsive behaviours. When modern technologies and substances exploit these systems, the resulting patterns can feel overwhelming.

If self-help isn’t enough, professional support is available. Speak to your GP, contact a helpline or access NHS services. There’s no need to wait until a situation becomes severe. Early intervention often makes change easier and outcomes better.